What kind of waste is polluting the beautiful beaches of Ostend? And what should the producers of that waste do to prevent the massive littering happening on the Flemish coast? That’s what we set out to investigate together with Proper Strand Lopers and City to Ocean, through a brand audit of the mountains of waste found on these sandy beaches.

Brand audits: what did we actually do?

Brand audits[1] are being carried out all over the world by thousands of volunteers and organisations with the shared goal of shifting the blame back to where it belongs: on the actual polluters, the producers and sellers of the waste that ends up in our environment.

In Ostend, you don’t have to look far to carry out such an audit. This summer, Proper Strand Lopers found up to 4000 L of waste during their daily one-hour clean-up. This sad news rightfully went viral on social media. How is it possible we let so much waste end up on our beaches and, eventually, the sea we swim in?

To determine where this waste was coming from, we gathered a sample of a day’s worth of litter to dissect its content. It was an average day at the end of the season (28th August), yet we still found 450 L of waste to analyse.

What did this mountain of waste look like?

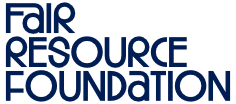

To answer this question, we pre-sorted waste per category to get a general idea of what it was made up of:

- PET bottles and cans: 160 liters (35%)

- No brand packaging: 110 liters (among which 0.5 L cigarette butts) (25%)

- Other branded items: 85 liters (19%)

- Parasols, toys and large objects: 80 liters (18%)

- Clothes: 15 liters (3%)

- Total: 450 liters

The share of plastic bottles and cans in volume corresponds to the general trend in Belgium. Together, they represent about 35% of litter.

Who are the biggest polluters of Ostend beaches?

Coca-Cola, Unilever and Lidl up for an unwanted medal

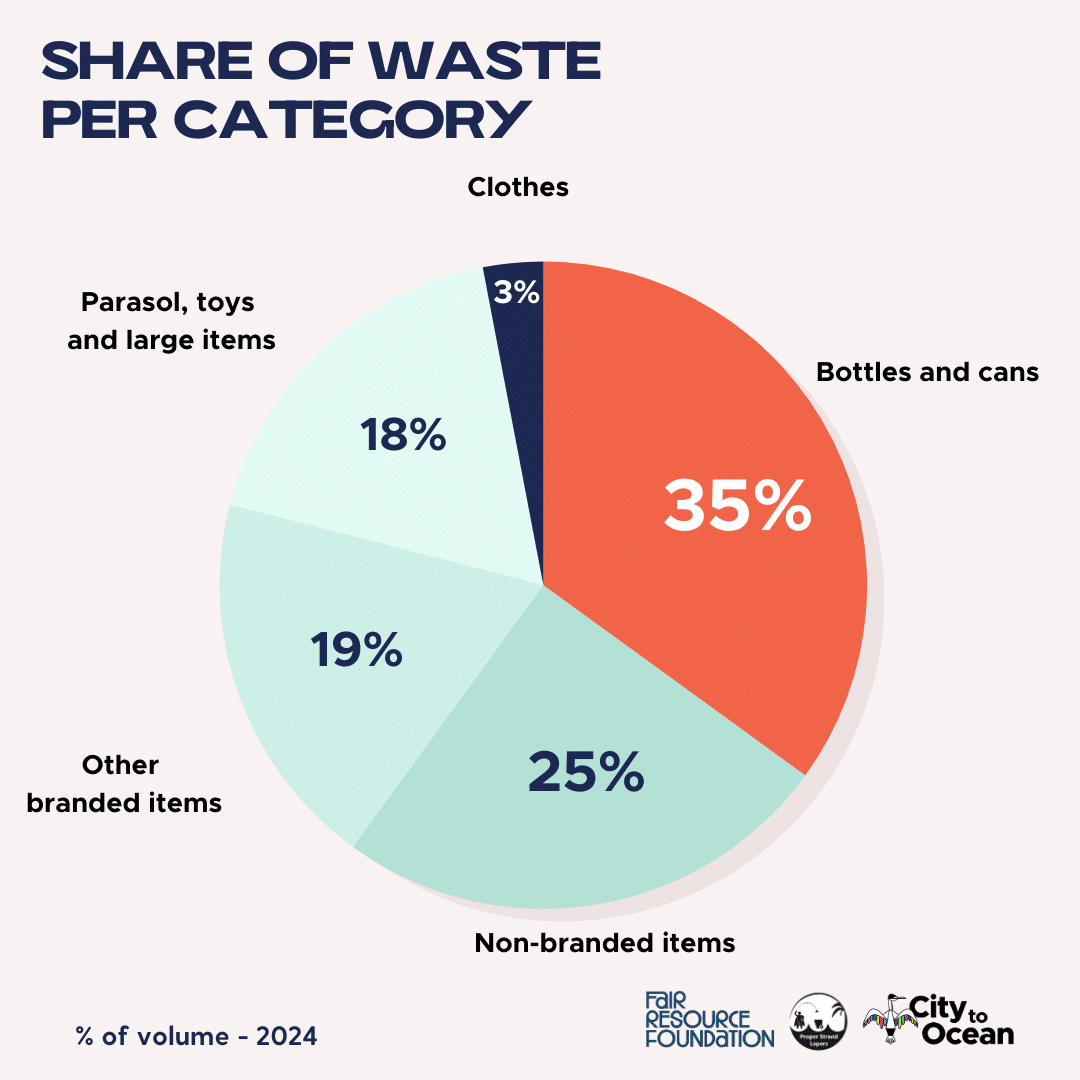

So who does the waste belong to? Figure 1 shows the 20 biggest polluters in item units.

On the tri-level podium:

- Coca-Cola (brands like Coca-Cola, Fanta, Fuze Tea, Innocent, Minute Maid and Sprite)

- Unilever (mostly ice cream brands Calippo and Cornetto)

- Lidl

Coca-Cola and Unilever are both listed within the top 10 polluters in the International brand audit of Break Free From Plastic. This has been the case for years, despite the brands’ campaigns to clean up their image. From Coca-Cola’s “Recycle me” campaign, to Unilever’s controversial green claims about recyclability and biodegradability, the two groups seem more eager to invest in marketing campaigns than into actual solutions to tackle littering (i.e. through deposit systems, decrease of single-use packaging…).

What is true worldwide is true everywhere in Belgium as well, with Coca-Cola already on the podium of the Brand Audit carried out in the Brussels’ canal by City to Ocean earlier this year.

Interestingly, supermarkets present in Belgium (Lidl, Colruyt, Aldi, Carrefour, Albert Heijn, Delhaize and Intermarché) are the owners of the brands representing 20% of all branded waste items we found during the audit in Ostend. They are doubly responsible: as producers of the packaging, but also as point of sale. Yet, the amount of initiatives in place in Belgium to reduce packaging in supermarkets are limited to a couple of inconclusive experiments and pilots. Our #EndDoublePackaging campaign highlights this lack of concrete action from supermarkets.

Note: in a brand audit, not every waste item has visible enough branding to be able to be linked to a specific producer or retailer. Whether it is because the labelling faded through long exposure to the elements or because the product simply doesn’t bear a branding.

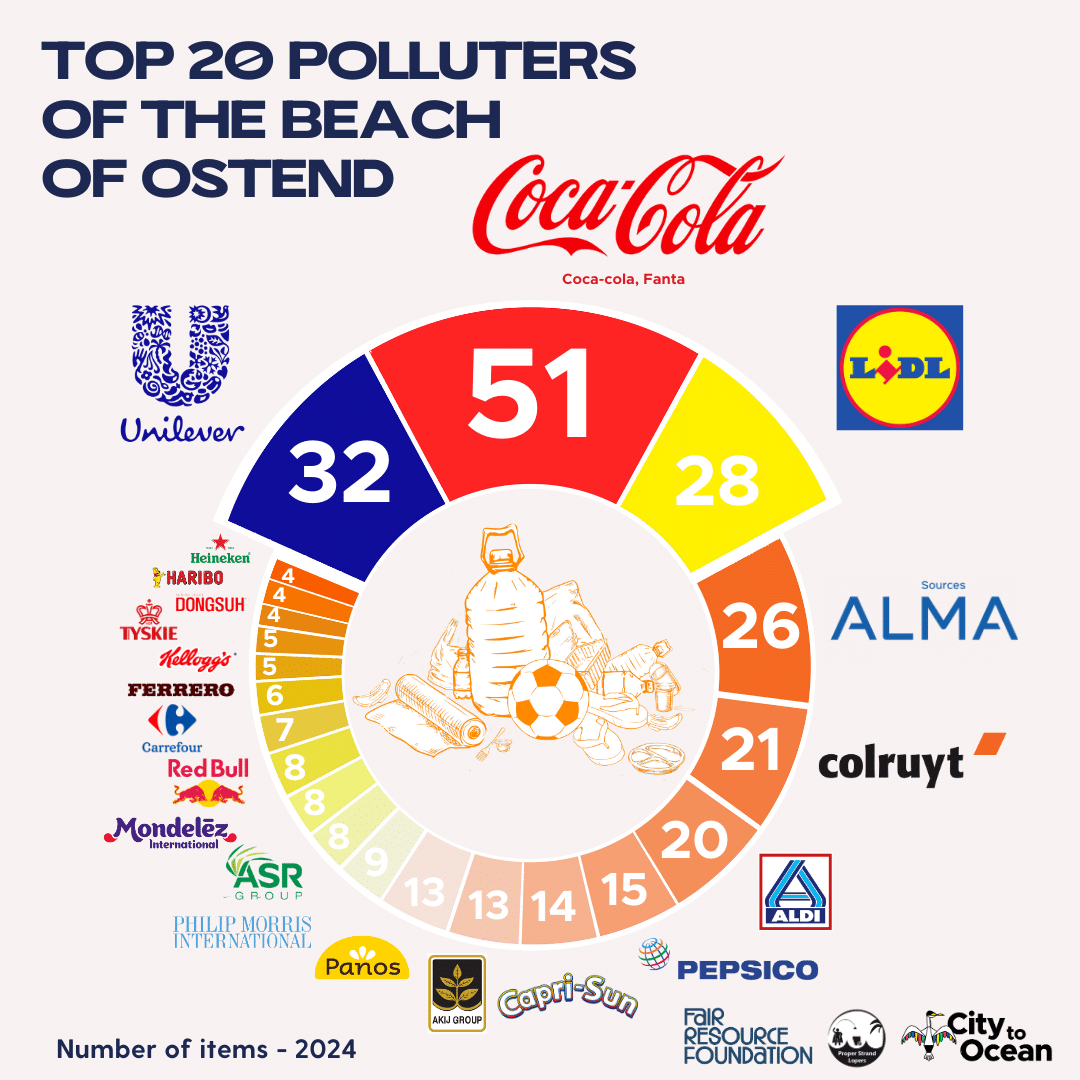

What is actually being wasted?

Plastic items represent 40% of all the litter found (in units). Next to the obvious plastic bottles, we found trays, food containers, drinking cups, straws, fruit and vegetable nets, all buried in the sand and washed ashore by the tide. This has a catastrophic impact on the local ecosystem and our health. The littered plastic deteriorates into microplastics that end up in the sand, in the sea, are eaten by animals and end up in our food and body. Several studies are raising the alarm on the presence of those microplastics in the human body (placenta, brain, blood), and we are only at the beginning of discovering the detrimental effect they have on our health.

Aside from plastics, paper-based items (cups, straws, cardboard food trays) are also increasingly found in litter. Although better than plastic when it comes to pollution (i.e. no micro-plastic, better degradability of the material), the production of paper-based packaging still has a large negative impact on the environment (EEB, 2023), including consequences such as deforestation, water scarcity and biodiversity loss. While shifting from plastic to paper can contribute to less plastic pollution, it is simply not as environmentally-friendly as prevention.

Deforestation is rapidly growing in Europe (Sweden, Finland) and South America (Brazil) due to the growing demand for paper packaging. Pulp production – used to produce cardboard packaging in Brazil alone represents 7.2 million hectares – twice the size of Belgium. On top of that, most paper-based items for food packaging still contain a plastic liner, which means we are still putting out plastic in our environment.

What is also appalling is that, whether it is on the Flemish coast or in the Brussels’ canals, the waste we find is always the same: The same plastic waste like food containers and individual wrappers, and the same carton cups and trays. Aside from a few variations – cigarette butts and paper napkins were less found in the Brussels’ canal – it’s the same waste over and over again. The same packaging, placed on the market by the same producers. Time for those producers to be held responsible.

From observation to action: Belgium, make the actual polluters pay

Identifying the problem is a great start but we need concrete actions from producers, and from the regional and federal governments, to solve it. Many solutions already exist to reduce the mountain of waste that threatens our environment and health. And no, those solutions do not stop at asking consumers to behave more responsibly when it comes to littering. Below, we list and explain a few of the many options to reduce litter.

Some measures can be applied directly to specific products :

- Cigarette butts – 30% of litter:

- Finalise the Interregional Cooperation Agreement on REP and litter so that cigarette producers finally pay for the cost of cleaning up tobacco products in litter.

Note: this agreement should be enforced since January 2023; - Use the SUP-tax to finance the placement of more ash trays in critical areas and create more awareness around the topic;

- Ban plastic cigarette filters to reduce some of the massive environmental impact of cigarettes (toxins, non-degradability);

- Finalise the Interregional Cooperation Agreement on REP and litter so that cigarette producers finally pay for the cost of cleaning up tobacco products in litter.

- Plastic bottles and cans – 10% of litter (35% in volume): introduce a €0,25 deposit on plastic bottles and cans. This solution has proven its effectiveness in 16 other European countries and will be mandatory in Europe from 2029. Deposit has been shown to reduce up to 90% of the amount of deposit-bearing packaging in litter.

- Paper napkins – 9% of litter : introduce an “on demand” system within HORECA so that consumers do not automatically get 20 napkins for a single meal.

- Plastic food packaging – 8% of litter:

- Extend the federal tax on single-use plastic drink packaging to all plastic food packaging to incentivize producers to reduce the amount of single-use items placed on the market and invest in reusable systems;

- Finalise the Interregional Cooperation Agreement on REP and litter at the interregional level so that the cost of cleaning up littered plastic food packaging is carried by their producers, instead of volunteers or municipalities.

Note: this is a requirement from the European Single-Use Plastic Directive which should already be transposed in Belgium since January 2023; - Ban packaging on most fruit and vegetables: other countries such as France and Luxembourg already took big steps in phasing out the plastic used to wrap fruit and vegetables. Studies show (WRAP, 2022) that this type of packaging is often unnecessary and only used to sell more products. It’s time to unwrap them.

General solutions: preventing over cleaning

Beyond those specific solutions per stream, we need a more general approach of packaging to reduce, rethink, reuse over cleaning up waste that end up in nature. Some solutions for Belgium include:

- Raising awareness on the overpackaging contact point managed by Fost Plus[2]. While Fost Plus has been tasked to improve this contact point in its new accreditation (art. 35), no additional communication seems to have been started. This is why we launched the #EndDoublePackaging campaign;

- Prioritising prevention and reuse to avoid packaging turns into waste in the first place. Only 2 reusable items were found among the 1400 individual items counted in the brand audit. Single-use items are inherently the ones ending up in litter. Regional governments need to ensure that producers, supermarkets and federations (Fost Plus, Comeos and Fevia) are prioritising the development of packaging-free and reuse solutions. Projects such as Circular Wallonia or Green Deal Anders Verpakt are a good start, but if as much would be invested in prevention and reuse as is currently being invested in new (chemical) recycling solutions, Belgium would be way further along in the transition to circular economy;

- Prohibiting the use of Green Claims such as “Planet Safe Plastic”. Products carrying these labels still end up as waste in nature and can have the unwanted side effect of making consumers less aware of the potential harmful impact of their waste.

- Forbidding packaging which are difficult or impossible to recycle in closed-loop such as pouches (CapriSun etc.).

- Force supermarkets to provide more bulk and refill systems.

In their new coalition agreement, both Flanders and Wallonia mention the “polluters-pay” principle, but unfortunately without any concrete measures. Together with this brand audit, we provide both governments with a list of clear actions that they can, and should, undertake to solve the problem.

Governments must take action and make producers take responsibility for the waste they create. Let’s finally shift our focus from cleaning up the mountains of waste that end up in nature, to preventing precious materials from becoming waste in the first place. It’s time to turn off the tap.

[1] We followed the methodology of Break Free from Plastic and submitted this brand audit for their yearly report (and included non-plastic categories as well). ↑

[2] Fost Plus is the Belgian household waste producer organization. It is responsible, on behalf of producers and retailers, to improve the circularity and environmental-friendliness of packaging for its members. ↑

Belgian packaging industry already saved 465 million € in litter fees – at our expense

The Belgian packaging industry is outraged by the introduction of a new €102 million litter levy. But it conveniently forgets that its effective lobbying has already saved it no less than €465 million. This sum has been gained at the expense of local authorities and society. This levy is due to be approved today by the Walloon Council of Ministers. Fair Resource Foundation delves into the figures.

Only 50% of cans collected again by 2023, political intervention needed

Press Release: Fair Resource Foundation response to Verpact’s new collection figures on deposit system

Study: tackling litter mainly helps producers of single-use products

Each region of Belgium has a different litter policy. Flanders has a -20% target for 2022 compared to 2015, which has not been achieved. In Wallonia and Brussels, agreements on litter are less clearly formulated and there is a lack of proper monitoring. In no region is litter tackled at the source.