In our previous article, we provided a wide overview of the size and importance of international plastic waste (PW) trade. Subsequently, in this piece, we will shed light on why plastic waste trade is such a profitable sector and which are the incentives to perform this business outside of legality.

Where does plastic waste end up?

In the last couple of years, an increasing number of news outlets are echoing news on the plastic sector and how tougher regulations on PW shipments are not enough to tackle the crisis in the PW sector. The crisis is caused by the fact that the recycling industry is struggling to compete with virgin materials, and the high volumes of plastic waste being traded from the EU into Türkiye and countries in South East Asia (which will be banned by 2026) instead of opting for national processing of the waste.

Newspapers – such as The New York Times – have recently released a number of investigative articles on the high amount of illicit shipments of PW from the U.S. with final destination in Malaysia. NGOs like Basal Action Network have managed to intercept the shipments. Within Dutch media, the Groene Amsterdamer published an interesting investigation revealing loopholes in the Dutch PW trade, especially emphasizing the case of Türkiye as an importer of Dutch and European PW. This month, the NL Times published an article revealing the low sentences bestowed upon criminals guilty of illicit plastic waste trade from the Netherlands to Asia and Africa.

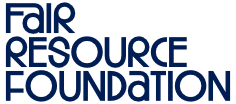

In 2022, the OECD[1] published the Global Plastics Outlook report where they revealed that in 2019, only 9% of all PW was being recycled, and almost a 1/4th part was being mismanaged. Mismanaging refers to when plastic waste is not recycled, incinerated, or kept in sealed landfills. Thus, it can either be burned in open pits, dumped into open waters, or disposed of in unsanitary landfills and dumpsites, which do not comply with regulations. Furthermore, they predicted that, at the current pace, by 2060 still 83% of PW will not be recycled but incinerated, landfilled or mismanaged.

Nevertheless, as we saw in our previous article, facts and figures within this sector vary drastically among sources due to the manifest lack of transparency by most actors involved. Aiming to shed light on this issue, the EU Commission will soon implement a comprehensive digital system, DIWASS (Digital Waste Shipment System), with the objective of monitoring all waste transboundary movements by all member states. While this initiative is important, we should also take a look at the way in which producers and consumers handle plastic waste, since the best way to reduce plastic waste trade is to lower the plastic item production at source.

Figure 1. Dutch plastic waste exports 2019-2060.

In this figure elaborated by OECD Global Plastics Outlook and reformatted by Statista (2022), it can be observed a prediction of the distribution of plastic waste through different waste management categories from 2019 to 2060.

As we can see in figure 1, most of the plastic waste is sadly not recycled. Out of the non-recycled share, roughly a ⅕ is incinerated, and the rest has to be stored somewhere. If we take into account that the landfilled part is more than 600 million tones of PW, a lot of space will be needed to store such a volume. It is then understandable why high-income countries would have incentives to outsource that burden to lower-income countries who can deal with it for a lower price. Trading poor quality or non-recyclable PW outside of the EU trade reports high benefit margins, but has been deemed illegal for a couple of years . As the ILT declared in a recent article by the Dutch newspaper NL Times, ‘at every step in the plastic waste supply chain, criminal activities take place’. There are loads of incentives to process the waste as cheaply as possible, even if it requires cutting down on processing steps necessary for its correct recycling.

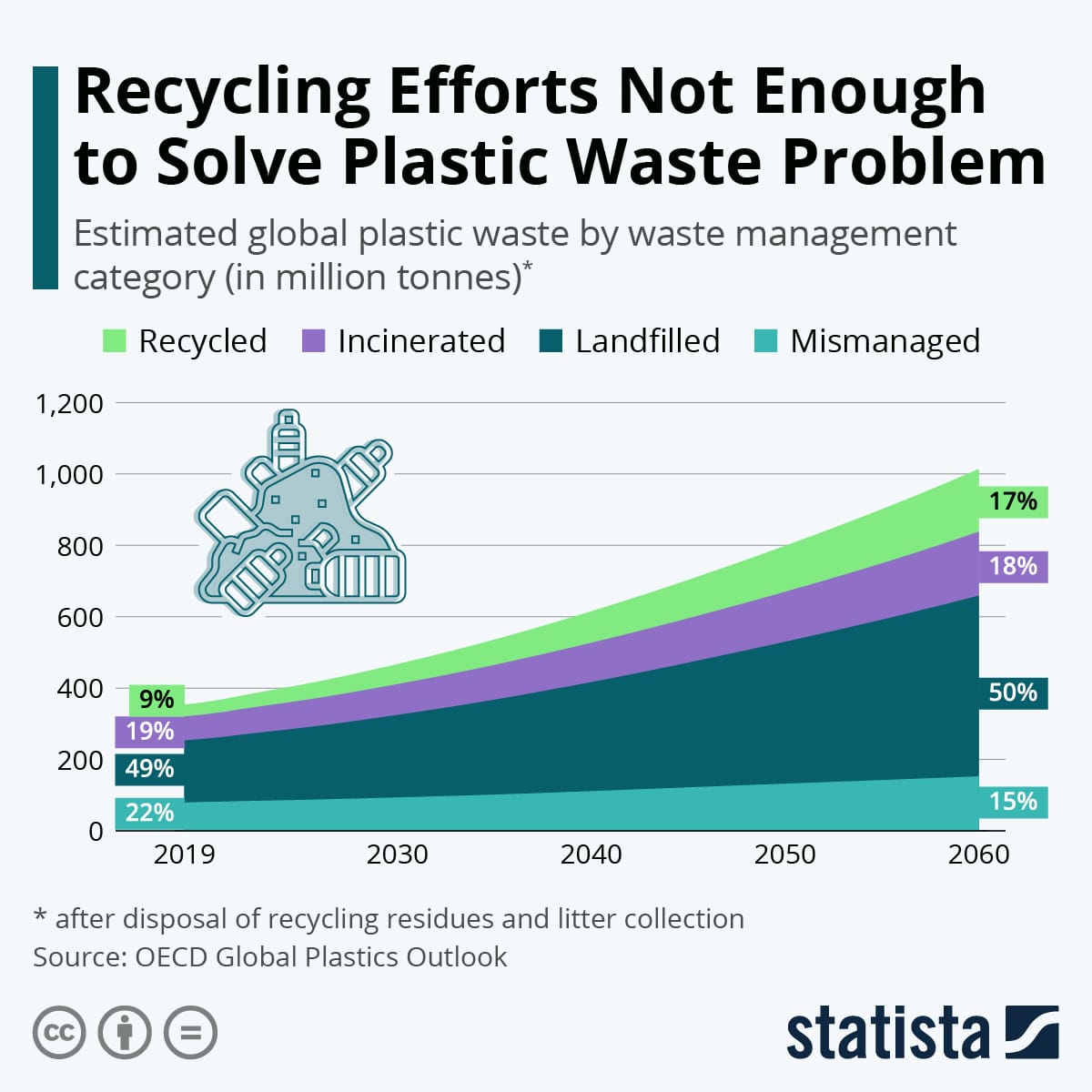

Despite increasingly restrictive regulation on PW trade and management from the Basel Convention and the European Union, the share exported outside the EU area continues to grow. According to ComTrade data, the final destination of Dutch PW exports has varied considerably in the last 5 years. In 2019, more than ¾ of PW exports stayed within the borders of the EU. In the following years, this number has been progressively decreasing. Most recent data from 2024 showed that in the last year roughly half of Dutch-exported PW remained in the European Union, and the exports to the non-OECD area had tripled. This data matches (with a variation of +/- 4 percentage points) with the estimations personally provided by the staff from Rijkswaterstaat (interview with Rijkswaterstaat advisor circular economy and waste, June 2nd, 2025). Nevertheless, according to all experts interviewed, the share of reported shipments (which are the ones counted in these figures) greatly differs from the total volume trade.

The fluctuations regarding export destinations are potentially due to a compound of factors, the main cause being unsure to us as of now. One partial explanation is the drastic decrease in shipping prices of containers from The Netherlands to East Asia. This is due to the high influx of fast fashion and other items from big online retailers such as Temu or Aliexpress. Full shipments of the latter goods are constantly arriving to European ports, but after unloading, the empty containers are required back to their origin in Asia. Thus, since the containers have to go back anyway, loading them with PW on their return ride is mutually beneficial for the PW traders and the exporters in East Asia, who need the container itself back either way. According to sources from ILT, shipping a container from the Rotterdam port to a country in East Asia currently costs around 150 dollars. That is a far lower price than the cost of shipping a container from a Northern Dutch port to Rotterdam. Therefore, shipping PW through this trade stream is cheap and does not raise suspicions.

Figure 2. Dutch plastic waste exports by destination, from 2019 to 2024.

In this figure elaborated by Fair Resource Foundation (2025), it can be observed the share of Dutch-exported plastic waste to three main receiving areas: European Union, Non-OECD (in this case Indonesia, Malaysia and Vietnam, the biggest non-EU importers of Dutch plastic waste), and Türkiye.

How does plastic waste trade work?

It all starts when the plastic is produced, because everything that is now waste, was in the past created and manufactured as a good, a commodity with positive economic value. You indeed paid for that plastic water bottle you bought at the station last week, right? Well, I hope you did. That plastic water bottle, a single-use plastic item, was created to be sold, used for a short period of time, and after that, it becomes trash. Waste usually is considered to have a negative economic value. For many waste streams, this holds true. However, although the intrinsic value might be negative, market mechanisms eventually decide whether there is an economic incentive for the handling of a waste stream.

In the Netherlands, the waste will eventually be collected by a waste management company. Depending on the municipality, it could also be pre-separated by the consumer into various recycling streams, or post-consumer separated. When it is post-separated waste, it will then ideally be sorted into recyclable and non-recyclable waste. The first should be taken to a recycling facility either within the country of collection or abroad (exporting it outside of the OECD will not be legally allowed from November 2026), and the latter incinerated or landfilled (exporting non-recyclable European PW outside of the OECD area is illegal since 2021).

Recycling companies buy recyclable PW to process it (chopping, washing, and melting it, in the case of mechanical recycling) and ultimately sell it as recycled plastic that can be used to make new plastic products. On the other hand, incineration and landfilling companies get paid to deal with the non-recyclable plastic waste (interview with employee of leading Dutch waste sorting and incineration firm, April 3rd, 2025).

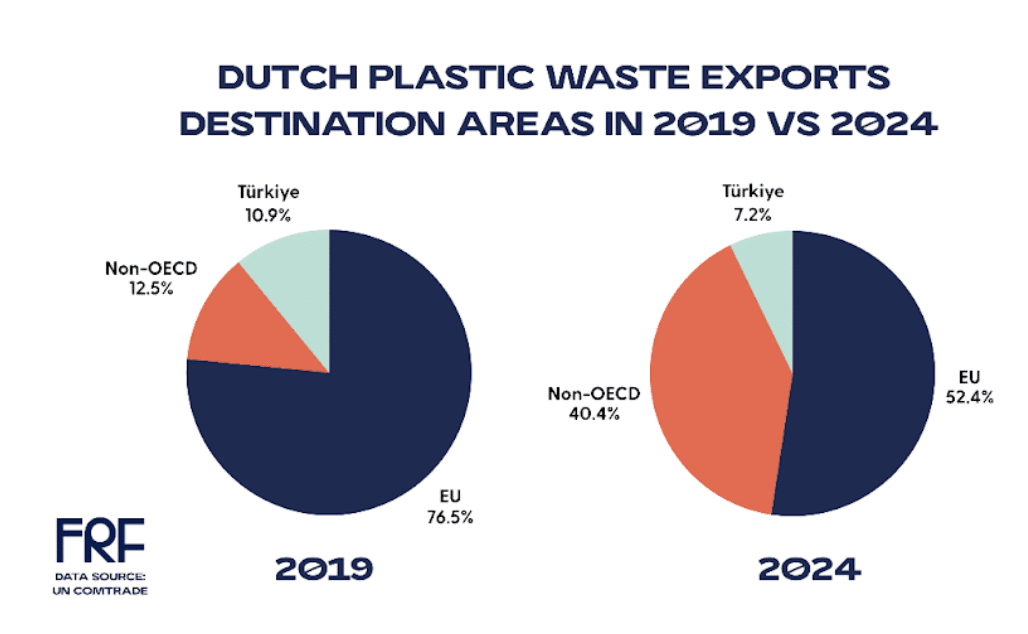

In the case of countries like the Netherlands, as seen in Figure 3, it is generally cheaper to outsource all of these processes to firms in lower-income countries, more if the final destination is in Southeast Asia (remember no country in that region is part of the OECD) or Türkiye, and even more if the trade is done illegally. Nevertheless, given the increasingly restrictive regulation on the sector, in a year’s time, PW exports to Southeast Asia (which currently receives around half of Dutch PW exports) will be entirely illegal.

Figure 3. Price of Dutch plastic waste exports by destination, from 2019 to 2024.

In this figure elaborated by Fair Resource Foundation (2025), the difference of prices of Dutch-exported plastic waste by area are shown: Non-OECD (in this case Indonesia, Malaysia and Vietnam), Non-EU (the later plus Türkiye), and European Union.

For years, the lack of comprehensive law enforcement, monitoring and inspection of shipments going through or being shipped from the port of Rotterdam makes it relatively easy to export PW cargo even if it does not meet regulation. The ILT (Dutch Human Environment and Transport Inspectorate), together with all the environmental experts we had the chance to talk to regarding the topic, pointed out that non-recyclable and contaminated plastic waste have proven to be smuggled through and from the Netherlands to various destinations, mainly Southeast Asia and Türkiye.

What are the incentives to smuggle plastic waste?

It is important to first note that the objective of smuggling PW is to get rid of it or manage it as cheaply as possible. Basically, smugglers of PW do not want their revenue to be hindered by ‘annoying’ environmental requirements that would certainly cut down their profits. Smugglers might send non-recyclable, low quality or heavily contaminated PW, or simply unsorted waste and declare it as clean and recyclable PW. Then the receivers may not be aware of the scam and find themselves with huge volumes of PW that have already crossed the world but do not meet the declared description and thus, cannot be recycled. The recipient countries see themselves having to deal with loads of foreign of PW which will not be recycled and will simply pollute their environment and cause serious damage to public health. The useless PW is sometimes sold as fuel for tofu factories, dumped in rivers, illicit landfills, or burned, releasing toxic smokes that are slowly killing the locals.

‘Tofu factories in the area (East Java, Indonesia) use plastic waste as fuel because it is cheaper than wood, even though the smoke from burning plastic waste produces dioxin which can poison humans, plants, animals and pollute the air . . . This happens each day in about 60 tofu factories in Tropodo . . . producing 60 tonnes of tofu distributed inside of Indonesia, including major cities.’ – The Guardian, May 2025

While sending PW to Southeast Asia or Türkiye does not mean that it will surely be mismanaged, evidence by different environmental advocacy groups (EIA, BAN, etc) have discovered many incidents of such illicit practices. Law enforcement in South Asian recipient countries is often weak and fines – if caught – are low. An alarming example is the Thai case in which the fine for illegal waste dumping is lower than the cost of adequate waste disposal. The low penalties for such crimes, together with lack of background checks for traders, are a huge incentive to seek benefits from this sector. This inconsistency enables perpetrators of such an environmental crime to have high benefits with little to no risk of facing serious criminal charges or even losing money.

Those who try to combat illicit plastic waste trade in receiving countries oftentimes suffer personally. Like the case of a Malaysian activist that has “received death threats, had her home splashed with red paint, her work and life disrupted, and was accused of having nothing better to do by the authorities – all in the name of protecting her home in Jenjarom” from illicit PW management turning her area into a toxic cauldron of pollution.

As we have seen, the PW management sector lacks fundamental transparency. The figures and specific processes on Dutch PW management and trade are not publicly accessible and interviewees within the industry were generally not willing to share further insights on the topic. It is important to notice that during the interviews conducted throughout this research, all partners from the PW industry we had the chance to talk with denied having ever come across illicit trade within the Dutch sector. Contradictionary, the rest of interviewees (non-industrial partners) declared having come across many cases of PW smuggling. Even so, during the writing of this article, a new case of it came to light in Dutch public news. In the month of August, several people were charged for illicit plastic waste trafficking from the Netherlands to Southeast Asia, Türkiye and Nigeria.

Looking ahead

After this short overview on the processes and profits of the plastic waste trade sector, let’s talk about legislation. As we brought up in our last article, in 2026 the EU will enforce a complete ban on plastic waste exports to non-OECD countries. This might be challenging for the Netherlands, which in 2024 reportedly exported more than 40% of its plastic waste to Indonesia, Malaysia and Vietnam, all of which are not OECD partners. Experts predict this ban may result in similar effects as China’s 2017 National Sword policy ban on all imports of PW . After China’s ban (which previously imported 72% of the world’s PW, and 85% percent of the EU’s) a lot of those PW shipments were redirected to different areas (Türkiye and Southeast Asia), still outside of Western Europe, resulting in the same problem. In the current case, Türkiye (already overflowed by foreign waste) has chances of absorbing a lot of that EU waste. Other sources from the Dutch ministry of transport predict exporters and traders to likely play with the definition of waste, as it is widely not standardized. This way a minimal step further after collection could imply PW being allowed to be categorized as (potential) resource for recycling instead of waste, and thus, be able to legally export it outside of the OECD area.

Big players within the Dutch PW export sector (as well as others across Europe) have declared they are hoping for the ban to be delayed (personal communications, April to August, 2025). Smuggling is likely to rise if the legislation comes to term given the imminent enforcement of the ban and the current inability of the EU to manage all the PW it produces. With the ban coming into place, the incentives for waste smuggling and dubious practices only become greater. Further research on the topic and enforcement of effective measures to tackle illicit PW is crucial. This increasingly restrictive regulation is great on paper, but as we have seen in previous years, it will serve very little if it is not implemented comprehensively. With no further strategies to tackle PW smuggling, dumping and burning, and higher incentives than ever given the EU ban and the current incapacity of Europe to manage its own PW, illicit trade is an increasingly big worry for the European Institutions and even more for countries in Southeast Asia and Türyike, already flooded with foreign PW.

Disclaimer: Due to the respect for our source’s privacy, Fair Resource Foundation has decided not to disclose the names of the interviewees participant in the present research.

Related Tags

Court of Rotterdam sentences several people for illicit plastic waste trade from the Netherlands

On Friday 8th of August 2025 Dutch news outlets echoed about a sentencing on plastic waste smuggling from the Netherlands to various non-EU countries. NL Times, AD, local news outlets, and the Dutch Inspection (ILT) reported the criminal sentencing of 4 people and 3 companies for illicit plastic waste trade, with one of them being also charged with money laundering.

Belgian packaging industry already saved 465 million € in litter fees – at our expense

The Belgian packaging industry is outraged by the introduction of a new €102 million litter levy. But it conveniently forgets that its effective lobbying has already saved it no less than €465 million. This sum has been gained at the expense of local authorities and society. This levy is due to be approved today by the Walloon Council of Ministers. Fair Resource Foundation delves into the figures.

Why is The Netherlands a key player in the global plastic waste market?

Despite its small size, the Netherlands is one of the world’s largest exporters of plastic waste per capita. Thanks to the port of Rotterdam and a strong trading position, the Netherlands acts as an important transit country – even for shipments with shadowy origins and destinations. A lack of enforcement makes the system vulnerable to illegal exports, with waste often ending up in countries with weak environmental regulations. This article shows how the Netherlands unintentionally contributes to global environmental pollution and why stricter rules and more responsibility are crucial.