Plastic waste (PW) trade is a major worldwide business involving big companies, small traders, waste brokers, law enforcement agencies, and governments from all around the globe. In 2023, reported global plastic waste exports were worth around 6.13 billion US dollars, profitability which the Basel Institute of Governance puts on a par with other major crime areas such as human trafficking. The dynamics within the sector are clear, PW shipments often flow from high-income countries to lower-income countries*. The recipient destinations, not equipped with adequate and/or sufficient waste management infrastructure, are commonly overflown with waste, having to manage foreign exports on top of their own domestic waste. In this article, we set out why waste trade remains so profitable for some actors, and why specific countries – such as the Netherlands – play a key role.

Most of these morally questionable PW flows have historically been permitted from a legal perspective. Experts estimate that around 25% of global plastic waste trade is illicit, going under the radar of law enforcement agencies and official reports. Illegal waste trade is the second most profitable environmental crime in the world, only after wildlife trafficking. This is what is known as high-profit low-risk crime. Waste has usually a negative economic value since it represents a cost for parties producing it if they will to safely and sustainably manage it. Therefore, there are incentives to find ways to reduce those managing costs by outsourcing the procedure. Shipping the waste to countries with less strict environmental standards, or simply illegally dumping it outside of authorities’ sight are the main modus operandi. Illicitly exporting PW is as simple as changing a number in the registration code of the shipment and hoping not to get checked by customs. As the Word Customs Organization declared in their Illicit Waste Report, the high profitability is caused by the weak enforcement of regulations at many trading points all around the world. The latter allows large volumes of recyclable and non-recyclable plastic waste to be misclassified and exported outside of the European Union into Türkiye and Southeast Asia. Such practices often lead ‘to lack of environmentally sound management, which poses severe pollution risks to air, water, and soil’. As many advocates for environmental justice have proved, European plastic is often found being burned in illegal dumpfields in countries such as Malaysia and Türkiye.

What is the role of The Netherlands?

The Netherlands is one of the highest-earning nations in the world. The Dutch economy is strong and highly focussed on trading thanks to its privileged geographic position at the heart of the EU, with access to international waters and great trading relations. Despite its small size, the Netherlands is one of the greatest per capita exporters of plastic waste in the world, each year ranking within the top 5 total PW exporter nations. The latest reports on the topic by scholars from Utrecht University show that a total of roughly 2000 kilotons (kiloton = 1 million kilograms) of plastic waste end up in Dutch territory every year. For reference, that would approximately be the same volume as 3.8 billion liters of water, more than 1,510 Olympic swimming pools full of PW.

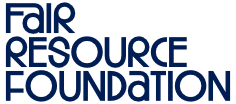

Figure 1. Dutch plastic waste imports and exports in 2017. In this figure elaborated by Lobelle et al. (2023), it can be observed the size of Dutch PW flows and which portion of them is reported.

In 2022, roughly 18.5% of worldwide plastic waste imports went to the Netherlands, a striking share given that the Dutch currently account for no more than 0,24% of the total world population. The majority of waste imported by The Netherlands comes from within Europe, mainly Germany, Belgium, United Kingdom, and France. Nevertheless, the final destination of Dutch PW imports is generally unknown and traceability is weak.

On top of the estimation that 25% of PW is being illegally traded, there are notable gaps in official data. For example, data from 2017 shows that a high percentage of Dutch PW (both imported and nationally produced) was blatantly unreported, and its location has remained a mystery for official sources. Experts from the Rijkswaterstaat declare ‘We know the data is not complete and there are large holes in it…we do not know what is happening with plastic waste streams…we cannot explain the differences between figures across official sources’ (interview with Rijkswaterstaat advisor circular economy and waste, June 2nd, 2025). Moreover, the Netherlands reported PW imports are over 300% of their remaining recycling domestic capacity.

According to the Dutch Human Environment and Transport Inspectorate (ILT), illicitly traded PW most commonly exits the country mixed with other materials or mislabelled as other kinds of goods, typically second-hand items, virgin materials, or already (partially) processed recyclable waste .

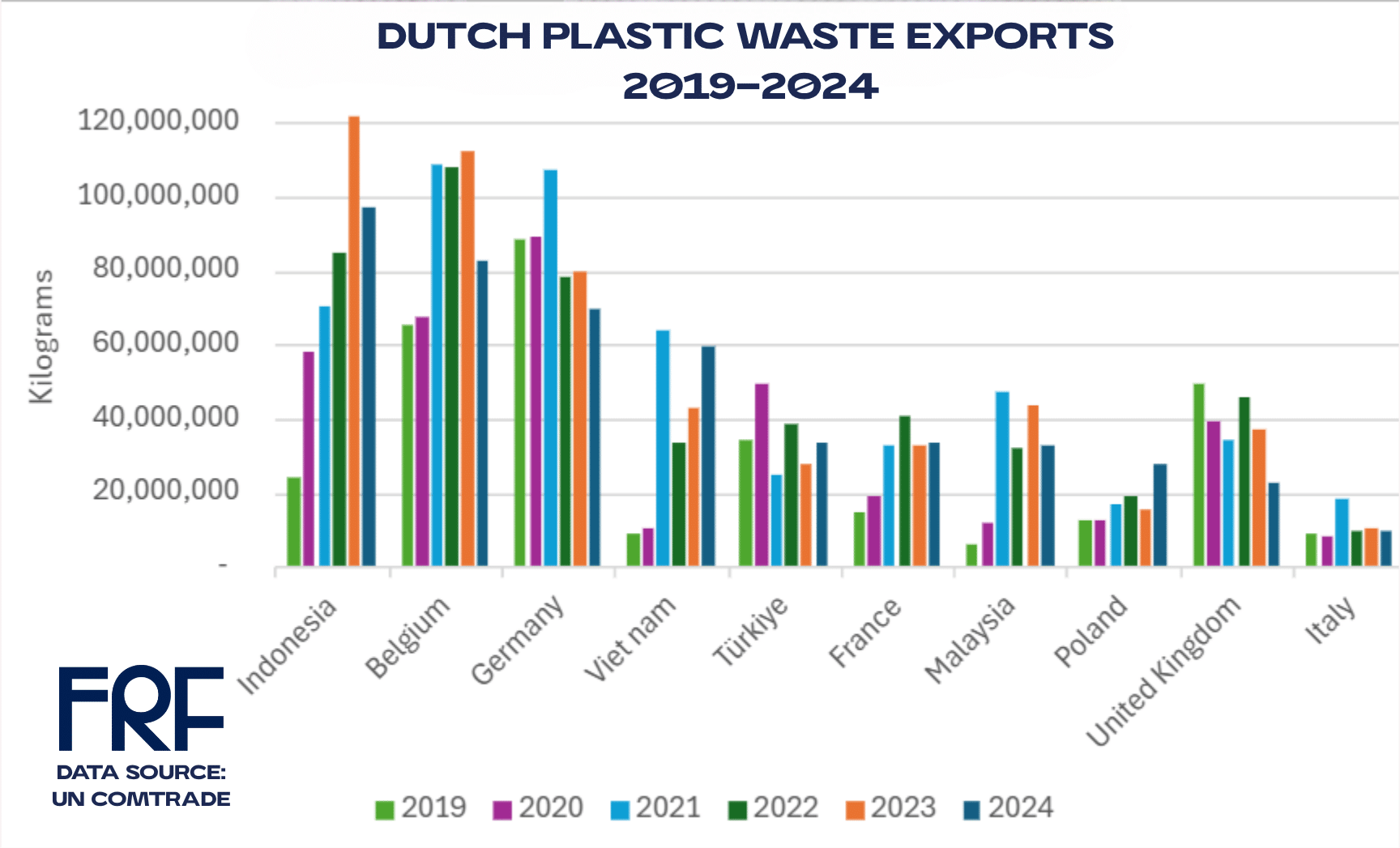

Even though exports widely declare only recyclable PW is exported outside of Dutch borders, experts on the topic declare that more than 60% of the PW imported by Türkiye is not recyclable (interview with PhD Marine Biology and expert on international plastic waste trade, April 4th, 2025). A concerning figure given the country imported more than 33 million kilos of Dutch PW in 2024. Nevertheless, the low prices paid by Turkish importers make it profitable to export large quantities of PW for very cheap. Thus, even if the portion of the shipment that can be recycled (and thus suppose a positive economic value) is limited, they are still able to make a profit. Nevertheless, Türkiye is not an isolated case and it is likely to happen in countries outside of the OECD area, which in 2024 represented more than 40% of all Dutch PW exports (see figure 2). Basel Action Network (BAN) and Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA) are NGOs currently working on the case and periodically publish reports on the matter.

Figure 2. Dutch plastic waste exports 2019-2024 based on ComTrade Data. In this figure of own elaboration, it can be observed the size of Dutch declared PW exports to its top 10 destinations.

Why does The Netherlands import so much plastic waste?

This is due to two main factors.

- First, the port of Rotterdam. This harbour in the South of the country is the busiest port in Europe, and reportedly one of the main exit points of waste shipments outside of the European Union. Therefore, the Netherlands is in a lot of cases not the final destination of this waste, but rather a transit hub on its way outside of the European Union. Around 40% of total Dutch plastic waste exports go to Indonesia, Vietnam, Malaysia, and Türkiye. Nonetheless, data on exact exports varies greatly among (official) sources. Moreover, containers often change ownership several times within their time at the port, hindering further the traceability of the PW shipments. The advisor for circular economy & waste of the Rijkswaterstaat declared that his agency is not able to explain the difference among sources, ‘the port of Rotterdam is a blackhole, we do not know what is happening inside, and the Rijkswaterstaat is not in active communication with ILT nor the port police or customs’.

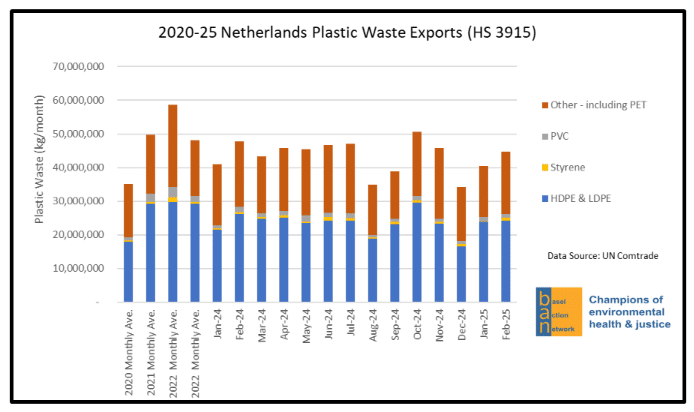

Figure 3. Dutch plastic waste exports 2020-2025. In this figure elaborated by Basel Action Network (2025), it can be observed the size of the monthly exports of Dutch waste to different areas.

- Secondly, despite the development of additional regulation on the topic, the lack of law enforcement causes both licit and illicit plastic waste exports to easily go through the harbour without being checked. In the Dutch case, law enforcement agencies and governmental authorities agree on the fact that the risk profile system, which determines whether a shipment is investigated, is not effective and excessively relies on the criminals ‘seeming’ suspicious. Customs in the Rotterdam port effectuate a total of 4,800 yearly checks on waste shipments, with only 13% being on plastic waste shipments. This represents just under an average of 2 checks each day of the year. Given the volume of the trade, this appears insufficient. Nevertheless, customs has up until now refused to participate in this research.

Looking ahead

In the meantime, the plastic market keeps growing at an accelerating rate, and Europe’s exports to non-OECD countries have grown 36% in the last two years. Nevertheless, things recently took a turn. In May of 2024, a new set of international regulations – the Waste Shipment Regulation – concerning the transboundary movements of waste was approved within the European Union. The enforcement of the new laws is estimated to start in 2026. Previous legislation allowed PW exports outside of the OECD area to facilities that could prove environmentally sound management of their imports. Nevertheless, the new regulatory framework will prohibit all plastic exports outside of the OECD area, thus aiming to cease all shipments to Southeast Asia. Other measures include the creation of an online international database of waste shipments seeking to increase the traceability of traded waste. However, the stricter regulation concerning PW trade with countries outside of the OECD has resulted in the divestment of shipments towards Türkiye (which is within the OECD area). Turkish imports of PW have been drastically increasing in the last years (see figure 2), as well as the number and size of illegal dumping spaces within its national territory.

Controversially, the European Union has intensively relied on outsourcing plastic waste outside of its borders and does not currently have the recycling capacity to keep up with the management of its own domestic plastic waste. Furthermore, in the Netherlands alone, 7 plastic recyclers closed in 2024. More than ever, Dutch PW exporting companies are in a chokehold. On one hand, they hope the implementation of the waste shipment regulation will get delayed (interview with CEO of Dutch leading plastic waste exporter firm, April 10th, 2025). On the other hand, there is no alternative destination or solution for continuing the export waste outside of the OECD area, making them fear a collapse of the market. It is now the task of Dutch law enforcement agencies to effectively implement the new regulation and better control licit shipment and detect illicit shipments. At the same time, the crisis in the recycling sector highlights the need to drastically lower the production of PW in all European Member States, in order to be able to deal with its own waste. Therefore, prevention and reuse strategies need to be scaled up in order to turn off the tap on plastic waste generation. Additionally, Europe needs to take responsibility for its own waste generation, instead of displacing problematic waste to other countries outside of Europe.

Disclaimer: Due to the respect for our source’s privacy, Fair Resource Foundation has decided not to disclose the names of the interviewees participant in the present research.

Linked tags

Packaging and Packaging Waste Regulation (PPWR) – an overview

The entry into force of the revised Packaging and Packaging Waste Regulation (PPWR) on February 11th 2025 brings large changes in the way packaging is managed in Europe. In this article, we give an overview of the main provisions of this Packaging regulation.

Reusable Packaging Fair 2024

After the success of the first Reusable Packaging Fair, we would like to invite you to the next edition on Tuesday 19 November 2024 at Congrescentrum 1931 in ‘s-Hertogenbosch. The Reusable Packaging Fair is partly organised by Mission Reuse, a collaborative project between Natuur & Milieu, Enviu and Fair Resource Foundation.

PFAS: the reason why chicken eggs are dangerous to your health

Amsterdam, 30 January 2024 – PFAS, the ‘eternal chemical’, is now everywhere: in our food, in our water and even in chicken eggs. How did this happen? Transparency International Netherlands (TI-NL) is investigating the root causes of this problem as part of its Weeffouten project.